We call ourselves “Anglican” because we inherit much of our theology and practice from the Church of England, which followed settlers into the New World during colonial times.

The Episcopal Church is part of the worldwide Anglican Communion, which is comprised of millions of members, located in regional and national member churches, in 160 countries around the Globe.

THE EARLY CHURCH IN ENGLAND

The English Church has a long history, dating back to apostolic times. Legend says that Joseph of Arimathea first brought Christianity to the shores of England. Whether or not this is true, British bishops were in attendance at the great Ecumenical Councils of the Church, beginning with the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

THE CELTIC CHURCH

Being relatively isolated from continental Christianity, the early Celtic church developed many of its own unique traditions and forms of governance, including, it is to be noted, very prominent leadership roles for women. In the interest of broader Christian unity, in the year 664 AD, at synod held in Whitby, Northumbria, hosted by the Abbess, St. Hilda, the Celtic church adopted norms and customs being used by the rest of the Church in the then-Roman World. The Celtic influence has never entirely disappeared from the Church in the British Isles; but from this point on, the Celtic traditions began to fade into the background.

For the next nine centuries, the British church lived and worked within the framework of what we know today as the Roman Catholic Church. In the time of the Whitby Synod, the Bishop of Rome was still regarded as the “first among equals,” among the bishops of the Church. By the late middle ages, the Bishop of Rome had become an imperial figure, above all other bishops. By the 1500s, the Bishop of Rome claimed universal jurisdiction over the entire Church. This proposition never set well with the English Church.

HENRY VIII

Although it was a contributing factor in the events leading to the institution of the Church of England, it is not true that the modern Church of England came into being because Pope Clement VII would not grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Arragon. (In point of fact, such requests were normally granted, and similar requests were granted by Clement. However, at the time of Henry’s request, Clement was a “guest” of Catherine’s nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose troops had sacked Rome.) Henry separated the English Church from Roman ecclesiastical jurisdiction in 1534. But Henry”s separation from Rome did not last. The English Church was rejoined to Rome almost immediately after his death. The separation which created the Anglican Church which exists today was not formalized until the reign of Elizabeth I.

Henry”s major contribution to what would become the Anglican Church was his appointment of Thomas Cranmer as the Archbishop of Canterbury. All that Henry was seeking in an Archbishop was someone who would grant a divorce from Catherine. What he got was an Archbishop who was sympathetic to the Reformation theologians, Martin Luther and John Calvin. In Henry”s time, worship was a very diverse experience from region to region in England. Liturgical practices were not unified, and even the language differed so greatly from place to place that liturgies used in one part of England could not be understood in another. Cranmer sought to unify the worship throughout England. He did this by creating the first Book of Common Prayer.

EDWARD VI

After Henry”s death, Edward VI became King of England and Ireland in 1547. Edward was too young to reign when he ascended the throne, and so Regents were appointed to rule for him. Edward”s Regents were devout followers of John Calvin and did much to firmly establish protestantism in England. Cranmer remained as Archbishop of Canterbury during Edward”s reign. But that came to a brutal end when Edward died in 1553.

QUEEN MARY

After Edward”s death the English Church was quickly rejoined to the Roman Church under the brief and bloody reign of Henry’s successor, Queen Mary I (1553-1558). One of Mary”s most notable acts was to have Cranmer (and 300 other protestant “heretics”) burned at the stake. Mary’s widely unpopular marriage to King Phillip II of Spain, and her vicious suppression of protestantism did more to bring about the final separation of the English and Roman churches than anything Henry ever did.

THE BIRTH OF ANGLICANISM

The Anglican Church as we know it today took its first form under Elizabeth I, beginning with the Act of Supremacy, formally separating the English Church from Roman jurisdiction in 1559. At this time, the English Church was struggling to find its identity. Traditionalists were working to maintain the traditions of the medieval Church against such Reformation influences such as Martin Luther and John Calvin. This came to a head in a bitter confrontation about how to read and interpret the Bible. In the midst of this clamor, the first uniquely Anglican position was first set forth by the theologian, Richard Hooker (1554-1600).

THE ANGLICAN WAY OF READING HOLY SCRIPTURE

Hooker argued for a middle way (a “Via Media“) between the positions of the Roman Catholics and the Calvinist Puritans. Hooker argued that both reason and tradition were important when interpreting the scriptures, and that it was important to recognize that the Bible was written in a particular historical context, in response to specific situations: “Words must be taken according to the matter whereof they are uttered.”

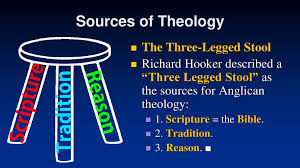

THE THREE-LEGGED STOOL

Scripture, tradition, and reason are often referred to as the “three-legged stool” on which Anglicanism rests.

The Holy Scriptures are the principle and foundational documents of Anglican Christianity. But, as Hooker argued, Anglicans believe that one must interpret scripture with an eye towards (1) how the tradition of the Church has understood it, and (2) using reason to understand the contexts and principles which the words of Scripture address. When looking to the tradition of the Church, Anglicans have always shown special deference to the first five centuries of Church teachings – before the rise of the Imperial Papacy. Together with Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches, Anglicans regard the doctrinal decisions of the Seven Ecumenical Councils of the ancient Church as normative interpretations of scriptural witness, especially as they concern Trinitarian and Christological doctrine.

TOLERANCE AND DIVERSITY – THE ELIZABETHAN SETTLEMENT

What has characterized Anglicanism from its beginning in the days of the Protestant Reformation is its toleration of diversity and its rejection of religious sectarianism. This meant that traditional catholic Christians, Lutherans, and Calvinists would all come to co-exist in the English Church, united by prayer and practice, rather than theology. As a practical effect, there was far, far less religious persecution in the British Isles than happened on the European Continent in the age of Reformation. This relative gentleness and toleration of diversity is a concrete fruit of the Via Media, or Middle Way, of Anglicanism.

Although Anglicans share a common approach to scripture, we are not defined by a common theology, but rather by common prayer. Our unity is not revealed in a shared body of doctrines, but rather in the shared practice and experience of worship. It is ultimately our experience of God and relationship to God — rather than our doctrines about God — that shape our common identity. Anglicans define themselves by a principle from the ancient Church: lex orandi, lex credendi –the rule of prayer is the rule of belief (Prosper of Aquitaine, ca. 390-455). Our faith is shaped and governed by our common worship, utilizing forms of worship that dates back to the earliest days of Christianity.

AN ANGLICAN BISHOP FOR AMERICA

Anglicans were among the very first settlers of the New World. But there were difficulties with the Church of England from the outset. The English never consecrated a bishop to oversee the church in colonies, preferring instead to keep control in London. After the Revolutionary War, American Anglicans sent Samuel Seabury to London in the hopes that he might be made a bishop for the newly independent colonies. But the English Church refused to consecrate a bishop who would not swear allegiance to the Crown. So Seabury went north to Scotland, where, in 1784, the bishops of the Scottish Church were all too happy to make him a bishop and send him home to the colonies.

The English Church eventually relented and consecrated two more bishops for the United States, William White and Samuel Provoost, in 1787. (William White, incidentally, also had the distinction of serving as the second United States Senate Chaplain, being appointed in 1790.)

AN AMERICAN CHURCH

The first General Convention of Anglicans was called in 1785, and the Protestant Episcopal Church, as it came to be known, was officially formed in 1789. This was the beginning of an independent Anglican Church in America.

In the meantime, Anglicans/Episcopalians played a major role in shaping the United States of America. Thirty-two of the signers of the Declaration of Independence (57% of them) were Anglicans. Thirty-one members of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 were Anglican/Episcopalians (56%). Nearly forty-five percent (44.8%) of the first Congress of the United States were Anglican/Episcopalians. Twelve (12) of this nation’s Presidents have been Episcopalian, beginning with George Washington. The influence of the Anglican/Episcopal Church in shaping American history has been and continues to be profound.

ANGLICANS IN SAPULPA

Good Shepherd Episcopal Church has been a part of the life of Sapulpa since 1901, when two devout lay persons, Mr. and Mrs. R. L. Mason, established a Sunday School in their home. The first church building was erected at the corner of Dewey and Walnut in about 1904. The parish moved to its current location, at 1420 East Dewey, in 1967.

COME WORSHIP WITH US

Holy Eucharist, sometimes referred to as ‘Holy Communion,’ or ‘the Lord’s Supper,’ is the principle act of worship in the Episcopal Church. Like the Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Roman Catholic Church, we use forms of worship — liturgies – that date back to the very earliest practices of the Church. (Justin Martyr, c. 100-165 AD, wrote a description of early Christian worship which reads very much like the Sunday worship bulletin at Good Shepherd!) The liturgies we use make heavy use of Holy Scripture, as well as prayers from the early Church and Anglican tradition.

You may find worshiping like the early Christians did a bit tricky at first. Over time, most Episcopalians learn the words and the prayers by heart, and worship becomes a time of prayer and reflection which grows deeper week by week. But even if the words and phrases of this ancient practice are new to you, you may be amazed to find how the Holy Spirit will speak to you through them if you approach worship thoughtfully and prayerfully.